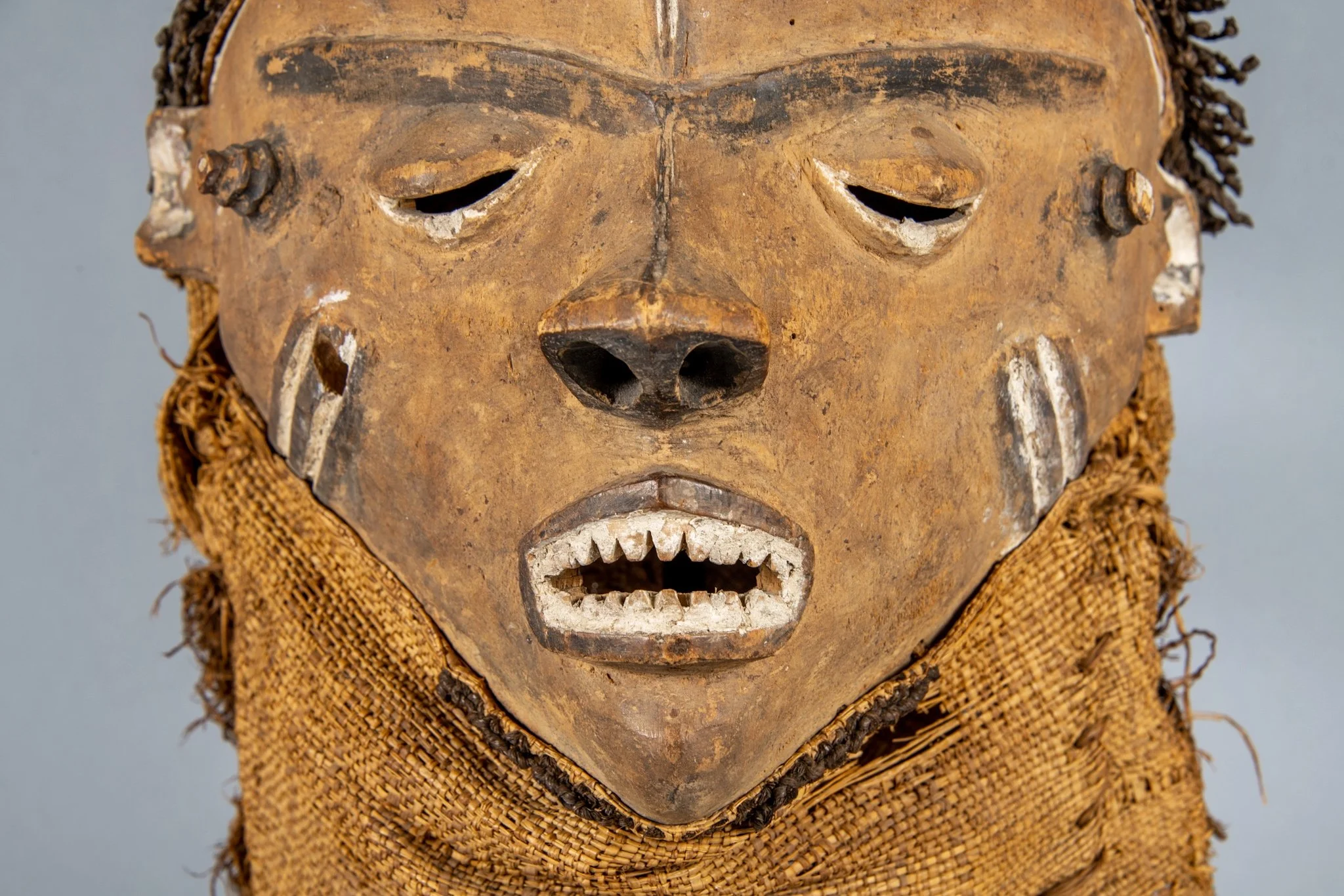

Pende ‘Fumu’ (the chief) mask

12” tall by 10” wide by 17” deep

Circa 1915-1930’s

Carved by Gabama a Gingungu (1895-1965)

Nkoya-Munene workshop, Kwilu-Kasai region, South-central DRC

Ex Isadore and Nancy Marder, US, purchased in the 70’s

Ex Edgar Beer/Alban Bronsin, Belgium

Ex Hendrik Elias, Belgium

Ex Galerie Khepri van Rijn/Lode van Riin, Netherlands

Published in ‘Hendrik Elias' Legacy’ by Jo de Buck (2018, pg. 30 figure 3)

Van Rijn Archives Object # ao-0037460-001

A very nice early example of a Fumu mask carved by one of the more well known and researched Pende carvers of the 20th century. Gabama’s Fumu chief’s masks are easily identifiable because of his specific stylistic characteristics on them, especially the nose and mouth as well as the unique characteristics of the headdress. The Royal Museum for Central Africa has a few of his masks in their collection, and Zoë Strother has identified several more.

A lot of early pre-colonial period Pende sculptors were also blacksmiths, and they spent a small amount of their time carving masks and sculptures. Once trade goods became available to the Pende that would have normally been made by the blacksmiths, and when Pende masquerades experienced an upswing, they spent more time carving.

Gabama a Gingungu wasn’t a blacksmith, and he grew up in a village that didn’t have any prominent carvers. People would often travel to other villages to have masks commissioned. When Gabama moved back to his mother’s village of Nkoya-Munene in the 1910’s his uncle, Maluba, was the prominent carver of the area. Gabama learned from him and soon surpassed him. At that time it was hard for sculptors to make a full-time living by carving alone, but Gabama and his uncle worked tirelessly and made reputations for themselves, but especially Gabama. “His nephew Nguedia Gambembo, who was also a sculptor, recounted that when all the masks in the village treasury were laid out, dancers snatched up all of Gabama's before they started on those made by Maluba (his uncle) or anyone else. By the 1920s Gabama had developed a reputation throughout Pendeland west of the Loange River, and some of his clients had to walk for several days in order to commission works from him.”

“It appears that the chief's mask (Fumu) was invented in the "dance-crazy north, probably in the 1910s, as a comedic mask. It is a favorite vehicle for older performers, who are loath to abandon the limelight despite a loss of flexibility. Its "dance" is composed of a mincing, highly stylized walk that kicks out the pleats of the chief's voluminous raffia skirt (Fig.8). For this reason, in one region the mask is nicknamed Mazaluzalu, "The one who floats. Performers flick the chief's fat flywhisks back and forth. The masquerader heads for a chair that has been set up in the arena, but is obliged to keep changing directions because helpers weave in and out, moving the chair in time to the drum rhythms. The performance gently parodies men who let the office go to their heads.”

“Gabama's chief's masks are a good subject for a discussion of the main grounds on which the sculptor's reputation rested: his mastery of physiognomy, that is, the ability to express inner character in the face. He is credited with expressing the full maturity of a stylistic revolution that took place in the north of Pendeland. The appearance of the chief's mask stabilized with Gabama because he offered such a perfect crystallization of what a chief should look like.”

Information in quotes from “Gabama a Gingungu and the secret history of twentieth-century art” by Z. S. Strother