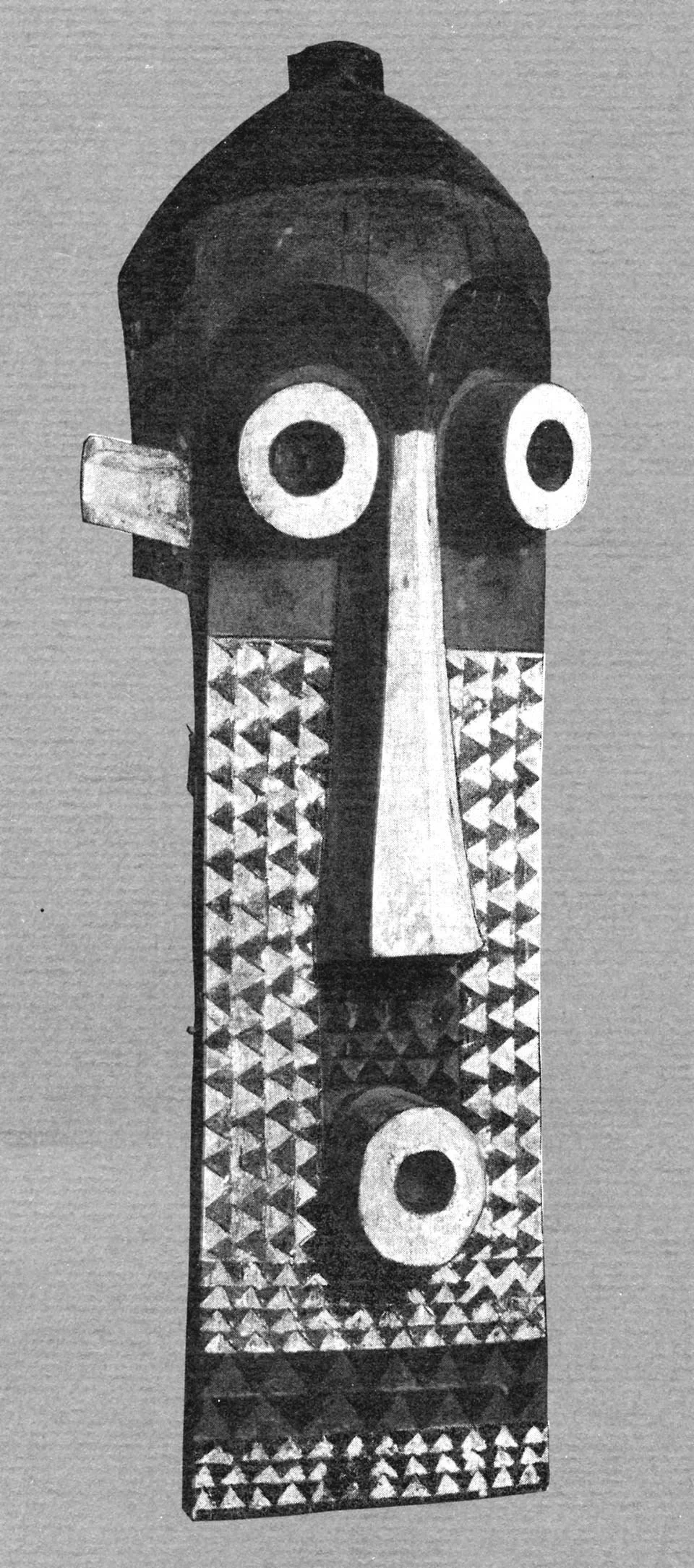

Eastern Pende

Pumu Ya Mfumu mask

Pumbu Ya Mfumu

"the chief's executioner" mask

Eastern Pende

30” tall

estimated 1940-1950’s

ex Carl and Wilma Zabel

ex African Art Museum of the S.M.A. Fathers, Tenafly, New Jersey.

ex NY collection;

Todd Zieseniss (agent)

The core of the SMA Fathers collections in NJ, about 250 works, was acquired between 1963 and 1978. With the exception of a few ethnographic pieces from Cadier en Keer, these early acquisitions came not from the European SMA museums, but from colonial collectors and dealers contacted by Father Hubert Jacoby. From the late 70’s - late 90’s the collections of the African Art Museum of SMA were greatly expanded in scope and depth. The efforts were enhanced and facilitated by the active involvement of Leonard Kahan, L. Kahan African Arts, who encouraged his clients to donate works to the collections. In the early 2000’s a long term plan was implemented at the museum, and a good number of objects were deaccessioned through a couple of small auction houses in NY.

Although these masks are documented in books, museums and private collections, they remain relatively rare amongst Pende masks. The masks represented the power of the chief, but only paramount chiefs reserved the right to own one. This was also the case with the panya ngombe masks and it adds to the rarity of both types of masks.

The designs on the lower part of the masks range from simplistic, like this one, to fairly elaborate. From looking at collection dates on documented examples it appears to me that designs on them became more elaborate post-1960 and were much simpler pre-1960. I don’t know exactly when this mask and its related dance first appeared amongst the Eastern Pende, but I haven’t seen any documented examples collected in the beginning of the 20th century. (I could be wrong). It’s my understanding that this style of mask evolved from or was inspired by the Kipoko/Giphogo mask style which is documented in the late 19th/early 20th century. The two masks share some stylistic similarities in the representation of the hair and ears, as well as the knob on top. These two masks, Pumbu and Kipoko, represent two two different characteristics of a chief. The Kipoko is peaceful and gentle while the Pumbu is aggressive.

Mouths are represented in different ways from circular to rectangular to somewhat more realistic representations, and most are represented with exposed triangular teeth since these masks have an aggressive nature in the dance they’re performed in. The bulging eyes with white rims are also a sign of aggression. The mouth on this particular example is unique and especially great in my opinion. At first glance it’s not very noticeable, but this mask has a shelf under the nose, which I’ve seen represented on a couple of examples, and the mouth is carved into the edge of the shelf.

The information below about Eastern Pende Pumbu masks is from the book “INVENTING MASKS: Agency and History in the Art of the Central Pende” by Z.S. Strother

“Among the Eastern Pende, PUMBU is also described as "the chief's executioner" (ngunza ya fumu), but the characterization of the mask is subtly different (than the Central Pende version). The Central Pende have developed PUMBU almost into a village character, interweaving his dance with songs related to the folkloric execution of a stranger during the chief's investiture. The Eastern Pende have transformed PUMBU into a counterpart of KIPOKO. If the latter represents everything warm and nurturing about the chief's role, the mask PUMBU depicts the courage that the chief must sometimes muster to address life-and-death issues. Like KIPOKO, PUMBU takes the form of a helmet mask resting on the shoulders, except that the "face" extends down to the performer's navel.

Whereas any chief may own KIPOKO, PUMBU is a mask reserved for a few of the Eastern Pende's most powerful chiefs. Unlike the other village masks, it dances only when special problems occur, such as a paramount chief's serious illness or a regional epidemic or famine. It often adopts the chief's own dress clothes (including blazers today) and circulates to subordinate chiefs and lineage heads to collect a small present as a form of tribute.

PUMBU performs holding a soldier's bow and arrow in one hand and a sword or machete in the other. He performs the kuhala kua ngunza, the "executioner's dance”, which is built around a walk with a stutter-step backward so that he progresses slowly, flourishing the blade in his hand. It is a dance meant to build tension as the executioner approaches his victim. Sometimes people do the kuhala before or after they slaughter an animal.

PUMBU strains against the cords that bind him to one or more young men. More young men accompany him, bearing whips and singing PUMBU's song: "Are you afraid?" The young men all come from the age grade that would be drafted if war were declared. At the climax of the dance, PUMBU whirls to cut the cords that held him in check. During a performance at Ndjindji, the crowd fled in terror, shouting, "Have pity, sir!" (Maleba, tata!) The men fled as well. Only the old chief Kombo was exempted.

PUMBU must kill something before he re-enters the chief's ritual house, where the headpiece is stored. Ideally, he will catch a chicken or goat that strays across his path. When this does not happen, the masquerade's organizers will bring something to him behind the chief's ritual house at twilight. At Kingange, PUMBU and the chief sat together in rattan armchairs behind the chief's house at twilight, overseeing the ritual sacrifice that closes a masquerade among the Eastern Pende.

The Eastern Pende have generalized PUMBU's signifiers by not referring to any one event or execution. By fusing with the chief, PUMBU represents the executive branch of his office, which must sometimes deal with war and execution. The Central Pende have particularized PUMBU by referring to one event. They have kept his identity separate from that of the chief's, although linked. Nevertheless, despite these differences, the distinctive core of the mask's dance remains identical among the Eastern and the Central Pende: PUMBU appears, restrained by cords, performing the kuhala dance by flourishing his sword. At the climax, he loses all patience and whirls around to cut the cord, at which point the crowd flees before him, beseeching moderation.

If TUNDU and KINDOMBOLO represent an antiesthetic, the two forms of the headpieces for PUMBU convey an aesthetic of fear. The chiseling and sharpening of the Central Pende physiognomy defined PUMBU's character as a hyper male. The Eastern Pende convey the same characteristics in a very different style through their emphasis on the protruding, white-rimmed eyes. Many Pende associate wide-open eyes showing lots of white with rage. The message of such eyes for both PUMBU and the whip-toting minganji is: get out of here or something awful may happen! Couched in very different formal language, the message of the two headpieces is the same: this mask is dangerous!”

Examples

I’m sharing these examples to show some the diversity of them.

Click on an image to see uncropped version.

Alain Bovis - Paris 2008

The American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY - acquired 1960. Bought by Mrs. Farysewski from a village carver in remote village S.W. of Tshikapa; made for local use, not for tourist trade. Museum's purchase (as Chokwe).

Archives Galerie J. Van Overstraete, Bruxelles

Galerie Didier Claes 2020

Image from 1972

Lempertz, Brussels, Belgium 2009

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Purchase, Nelson A. Rockefeller Gift, 1968. Henri Kamer (1927-1992), Cannes/Paris, France, New York, USA, until 1968. The Museum of Primitive Art, New York, 1968–1978

Native Auctions 2018

Private collection

Smithsonian. National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C Gift of Walt Disney World Co. Paul and Ruth Tishman (1900-1996 & 1905-1999), New York, USA, pre 1970-until 1984

Sotheby's 1998